One Century of Moulin-a-Vent and Château des Jacques

Both Château des Jacques and the prized vineyard celebrate 100 years

Everyone loves an underdog story – David vs Goliath, Rocky, The Karate Kid… and Gamay Noir? Gamay Noir (and as an extension, its ‘home’ region Beaujolais) is seeing somewhat of a deserved renaissance at the moment and it couldn’t come at a better time – Our Dhall & Nash corner of this storied region resides with one Château des Jacques, a storied estate with ties to the very first official Beaujolais Cru, the 100-year-old Moulin-à-Vent Appellation – both celebrating the momentous milestone this year.

“Moulin-à-Vent is certainly one of the finest of the Beaujolais crus, yet remains under the radar.”

– Andy Howard MW (Decanter)

But without further ado, it’s time to put our birthday-vineyard – Moulin-à-Vent – into the limelight.

We’ve covered Beaujolais and Chateau des Jacques in great detail before, for those who prefer an in-depth rummage around all the subject’s nooks and crannies can have a field day learning about carbonic & semi-carbonic maceration, pink granite, it’s ties to Burgundy, Gamay and why Beaujolais Nouveau is not the be-all-and-end-all of this region… [read more]

Happy Birthday, Moulin-à-Vent!

17th April, 1924

Moulin-à-Vent’s official ‘birthday’ is 17th April, 1924.

At the time, it was lumped into Burgundy as an AO (“Appellation d’Origine”) as “Romanèche-Thorins” (the township) to counter the rise of fraudulent wines as reputation started to grow (In 1924, the wine from ‘Moulin-à-Vent’ was sometimes valued higher than Grand Cru Burgundy!) Then when the Beaujolais AOC was established separately in 1936, Moulin-à-Vent was the very first official cru.

“Arguably the most prestigious address in the appellation…”

– Kate Hawkins (The Buyer)

Moulin-à-Vent

Moulin-à-Vent literally means ‘windmill’ and was named for the local windmill, standing proud at 278 above sea level and 5 and a half metres tall since 1550.

“Everything begins with the osmotic relationship between the vines and the soil in which they’re planted”

– Château des Jacques

Moulin-à-Vent is nicknamed “The Lord of Beaujolais wines” because of its noble bouquet and it’s considered the sturdiest, most tannic, longest-lived among the 10 Crus of Beaujolais. When you hear about folks opening up delicious bottles of 50-year-old Beaujolais, it’s usually Moulin-à-Vent. But remember, we are still talking about Gamay. The wine is never that tannic, and most examples are still very approachable when they’re young, unless the vintage is a particularly structured one.

“The best wines of Beaujolais can easily rival Burgundies that cost many times more.”

– JancisRobinson.com

What’s Next for Moulin-a-Vent?

At 100 years old, a human would be winding down at the very least, enjoying a leisurely life after a century of activity, but this milestone is just the start for this Beaujolais player – the appellation is hoping to elevate its status to premier-cru.

Edouard Parinet of Château Moulin-à-Vent (not a part of Château des Jacques but a cool neighbour) explained to James Lawrence of Wine Spectator that they have “petitioned the INAO [the government body charged with regulating French agricultural products] to elevate 14 lieu-dits to the official status of premier cru. The vineyards in the appellation are: Aux Caves, Michelon, Carquelin, Champ de Cour, Chassignol, la Roche, la Rochelle, a Tour du Bief, le Moulin à Vent, les Perelles, les Rochaux, les Thorins, les Vérillats, and Rochegrès. As part of our proposal, we have mapped out a new framework that will regulate how growers manage these plots. This includes a prohibition on synthetic chemicals in the vineyard, lower yields, and a delayed bottling and distribution of the wines on the market.”

“100 years after it was first recognised, the appellation of Moulin-à-Vent in Beaujolais is now seeking premier cru status for its finest sites. Andy Howard MW says it is long overdue.”

– Decanter

Happy Birthday, Château des Jacques!

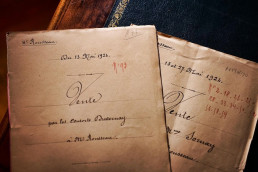

27th May, 1924

Shortly after the Moulin-à-Vent vineyards were basking in their new official AO glory, one Amédée Rousseau purchased Château des Jacques, which really marked the beginning for this storied estate. Kate Hawkings for The Buyer explains, “Built in the 18th century, the château had been the second home of the Sornay family, whose upwardly mobile children showed no interest in keeping it and its two hectares of vineyards. Below it are impressively vaulted 17th century cellars, suggesting it had once belonged to the church and likely to have been a hostelry for pilgrims to Santiago de Compostela which probably gave it its name.”

Rousseau was a visionary French entrepreneur and wine enthusiast of humble beginnings, born to a miner father and laundress mother, who would dedicate the last years of his life to the creation of his dream-wine estate – Château des Jacques. Patiently, for three years after the purchase, Rousseau acquired over 70 more plots in Moulin-à-Vent from 60 different families.

“Rousseau was also the first in the region to de-stem his grapes, giving them long macerations and ageing in barrel, recognising that the taste of consumers was changing… This distinctive Château des Jacques style remains to this day.”

– Kate Hawkins (The Buyer)

The Thorin family, which succeeded Amédée Rousseau after his death in 1931, defended with conviction this vision of his beloved and noble Gamay, capable of producing complex, bright wines with significant ageing potential. It didn’t change hands again until 1996, when the Thorins passed on the Château to the Kopf family of Maison Louis Jadot renown, who are now working to implement sustainable practices, renovating vineyards, widening rows and experimenting with some whole bunch fermentation.

“If you want to really spoil yourself a glass of Moulin-à-Vent, Château des Jacques Clos de Rochegrès demonstrates just how good Gamay gets…”

– Matthew Clark (matthewclark.co.uk)

Château des Jacques Moulin-à-Vent Clos de Rochegrès 2017

361 metres above sea level, Clos de Rochegrès is the last of the Moulin-à-Vent parcels to ripen. The soils are not deep but contain more clay than those of Carquelin or la Roche, and quartz are omnipresent.

Opulent and generous, this vineyard selection is one of the best wines of the appellation. Picked and sorted by hand, then mainly de-stemmed, the grapes macerate slowly over the course of three or four weeks. Indigenous yeasts are used throughout the fermentation period, and extraction by means of both plunging and pumping over takes place on a regular basis. The wines are aged in the Château des Jacques historic cellar for 10 months, a period spent in oak barrels, both old and new. The wine can then age comfortably for several decades.

92 Points (The Wine Advocate)

“A wine built for the cellar, the 2017 Moulin-à-Vent Clos de Rochegrès unfurls in the glass with a rich bouquet of ripe berry fruit, spices, candied peel and dark chocolate. On the palate, it’s full-bodied, rich and concentrated, with an ample core of fruit, ripe acids and a chewy chassis of tannin that will require some patience. Impressively, this Moulin-à-Vent has already largely integrated its new wood, and though it’s a high wire act in terms of alcohol and extraction, I suspect it will evolve positively in the cellar. Drink 2022-2040.”

94 Points (Wine Enthusiast)

This wood-aged wine comes from 45-year-old vines in one of the top vineyards in the appellation. Rich and beautifully structured, it has tannins and a firm structure that point to ageing.

Château des Jacques Moulin-à-Vent La Rochelle 2018

Located just a few steps away from the windmill itself, this south-facing slope offers the Gamay vines a deeper, more broken down granite soil than the other ‘climats’ that encircle the historical monument.

“La Rochelle” always has a particular richness and concentration, regardless of the vintage. Even though its richness and concentration are remarkable , this wine still shows a typically Burgundian elegance thanks to its fine tannins. Picked and sorted by hand, then mainly de-stemmed, the grapes macerate slowly over the course of three or four weeks. Indigenous yeasts are used throughout the fermentation period, and extraction by means of both plunging and pumping over takes place on a regular basis. The wines are aged in the Château des Jacques historic cellar for 10 months, a period spent in oak barrels, both old and new. The wine can then age comfortably for several decades.

92 Points (Bob Campbell)

Soft, fruity, gamay with mellow, flavours that suggest ripe plum, cherry, and a seasoning of spices. Accessible now but no hurry. Seductive texture, not particularly powerful but delicious to drink.

The Burgundy Report

A more higher-toned nose – more fruit-focused and redder fruit. Extra fresh – cool fruit – mouth-filling – the best texture yet. Once more, a great finish – persistent and concentrated – bravo!

Gamay - An Underdog Story

Everyone loves an underdog story – David vs Goliath, Rocky, The Karate Kid… and Gamay Noir? There’s no doubt that Pinot Noir is the golden child of the Eastern vineyards of France, and for a long while its brother, Gamay Noir has been somewhat overshadowed, and sometimes even publicly slandered…

Beginnings: Once upon a time, Gamay Noir was planted alongside its brother, Pinot Noir, all over the limestone-rich hills of Bourgogne. Winemakers liked it as it had high yields, was picked earlier and could be enjoyed young, so it was the chosen ‘quaffer’ of the time.

The First Fall: In the fourteenth century, Philip II the Bold (the Duke of Burgundy and son of King John II of France and Bonne of Luxembourg) banished Gamay Noir south, dubbing it “evil,” “foul,” “disloyal,” and even “injurious to the human creature”, making room for Pinot Noir to inhabit all of the “superior” hillsides of Burgundy proper. Following authorities doubled down on this, with reiterations of the ban being issued in 1455, 1567 and several times during the 18th century.

This turned out to be a blessing in disguise for Gamay as it produces a much better wine in the granitic soils of Beaujolais, compared with the limestone escarpments of the Côte d’Or.

The Slow Rise: Over time, the quality of the Gamay coming from the south spoke for itself, and by the early 20th century Beaujolais – particularly those from Romanèche-Thorins/Moulin-à-Vent – were very in vogue, collected and enjoyed by those even over and above some Burgundy Crus.

“Parinet hands me a photograph of a very old wine list printed in 1928. You can imagine where it came from: a bustling Parisian brasserie full of garçonnes (flappers), surly waiters, and cigarette smoke. On the menu is a Château Moulin-à-Vent 1923 to accompany your canard. Amazingly, it is offered at a higher price than either the 1924 Beaune or Pommard. Likewise, a bottle of Hermitage and Côte-Rôtie were both cheaper propositions back in the Roaring Twenties. Beaujolais as the pricier option? Who knew.”

– James Lawrence (Wine Searcher)

With quality came counterfeiting, and so the introduction of the AO (100 years ago!) and AOC (88 years ago) aimed to put that behind them.

What goes up (again) must come down (again): Much like Chardonnay’s ABC movement, sometimes it’s simple misunderstanding that foils the grapes’ ascension.

Throughout the mid to late 20th century, despite wonderful experimentation from the likes of Jules Chauvet – a négociant, oenologist and chemist from Beaujolais widely considered to be the godfather of natural wine – the “Bo-Jo” (Beaujolais Nouveau) wines were the ones most people were exposed to. These were the wines released on the third Thursday of November in the same year as the vintage. Originally it was a simple drink to celebrate the end of harvest. That idea grew to become a global marketing success peaking in the 80’s. But crucially, it’s meant to be drunk young, and it’s meant to be flirty, fruity, and fun! Which it was – and which has its place – and so production increased (often at the cost of quality).

But too many people drank it thinking it was meant to be a serious wine, when it really wasn’t, leading to a general-populous dismissal of Beaujolais and Gamay as a fruity party-quaffer that left sommeliers and vignerons clawing at their faces wanting scream from the rooftops about the real beauty, potential and diversity of Beaujolais.

Renaissance: When it purchased 200-acre Château des Jacques in 1996, négociant Louis Jadot became the earliest arrival to the region from modern Burgundy. Ownership of the company was attracted by the possibilities of the Gamay grape and the comparatively inexpensive land. It is now widely recognized as the most prestigious estates in Beaujolais.

Over the intervening years, Château des Jacques’ practices have been in line with the previous trail-blazing owners, and have been attributed with revolutionising the winemaking of Beaujolais. They have notably raised the bar, applying Burgundian methods of winemaking that were once traditional in the region. These include long macerations of one month, with pump-overs, to extract colour, aroma, and tannins from the fruit, as opposed to the regional norm of 10- to 12-day macerations. Wild yeasts are used for fermentation, and this is extended longer than is typical in Beaujolais. Ageing in oak barrels was also unusual for the area; Château des Jacques’ wines are barrel aged for 10 months to lend complexity to the wines.

Now, it’s about as hip as it gets. Like we said, people love an underdog story, and this grape-next-door is seeing vindication centuries in the making.

“I love Beaujolais, and the gamay grape from which it’s made. I love how it sits so perfectly, stylistically, between the lighter-bodied, more ethereal pinot noirs of Burgundy (further to the north again), and the fuller-bodied, darker, more structural syrahs of the Rhône Valley to the south of Lyon. I love how its medium-weight-but-gutsy character makes gamay such a versatile wine on the table, matching everything from the lightest fish dishes and salads to the richest, stinkiest sausages.”

– Gourmet Traveller